Any claim of personal property is deferential to the concept of ownership; the right to exclude. The Constitution of the United States makes reference to the State’s property in Article IV, and to personal property in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments but no definition is given there as to what property is, what constitutes ownership, how it came to be, or how one person or government could obtain the right to exclude another from the use of a common resource e.g., a part of the Earth and claim it as real property [1].

In his Second Treatise of Government, Locke put forward his reasoning regarding the right to property. His arguments are a logical progression from one link to the next—every link must hold or the entire logical chain fails; beginning with the understanding that the natural state of ownership is ownership in common, and expounding upon that principle with the claim that from the state of common ownership, exclusive ownership of a thing can be justly established, extended, and then lost again.

…once King George III’s power was appropriated, it immediately fell into the hands of the wealthy planter elite. Four of the first five presidents were wealthy owners of large plantations

Locke begins his logical progression with the concept of human liberty—the idea that every person owns themselves, and therefore owns the productivity and value of their own labor. “Though men as a whole own the earth and all inferior creatures, every individual man has a property in his own person [= ‘owns himself’]; this is something that nobody else has any right to. The labour of his body and the work of his hands, we may say, are strictly his” [2]. This concept can be practically illustrated, with the narrowly defined ownership of self. A person who engages in physical exercise is the sole beneficiary of the resulting improvement in physical fitness; and Locke argues further, that even when a person acts on common resources to make them more fit for some purpose, the person is entitled to be the sole beneficiary of the value of their productivity, particularly in terms of the rights of ownership.

Thus far, this discussion narrowly addresses claims of ownership in terms of the value of productivity, based on Locke’s logical progression of ownership as such; a person owns themselves [3], thereby owning their labor, thereby owning the value their labor produces. Following this path of logic, when a person adds the value of their labor to a resource that is owned in common, by virtue of their investment, they own the value they contributed, but not the value that was extant before their labor was added, e.g., if a person adds value to an asset that is owned in common, the asset is still owned in common, and the person who added value has increased their own equity in the increased value of the asset, proportionate to the value that they have added.

Locke says, “So when he takes something from the state that nature has provided and left it in, he mixes his labour with it, thus joining to it something that is his own; and in that way, he makes it his property” [2]. Locke’s leap of logic here is that the common resource has no value until labor is added to it—in such a case, any value added by labor would constitute 100% of the value of the resource; so, the person who created the value, by way of their labor, can claim all of the value of the resource, i.e., the resource becomes their property. Locke qualifies this position by balancing abundance with frugality. “Anyone can through his labour come to own as much as he can use in a beneficial way before it spoils; anything beyond this is more than his share and belongs to others” [2]. His logical extrapolation in this argument is that there are enough common resources for everybody if they consume resources responsibly.

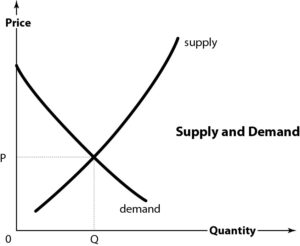

The qualification of responsible consumption is implicit recognition that the common resource is finite. That being the case, the value of a finite resource is subject to the relationship between the supply of it and the demand for it. As a finite resource is consumed, the remaining supply diminishes, and relative demand is increased, along with price or present value. This relationship is illustrated by the supply/demand diagram. The x and y axis represent quantity and price respectively and increase from a value of zero as they move away from the origin.

Locke’s arguments are based on supply at its furthest from the origin, where supply is at its maximum and value is near zero (the demand curve approaches the zero price point), but as a finite resource is consumed, and supply approaches zero, the value of the finite resource, is great (the demand curve is at its highest), even before any added value resulting from human labor. This reality presents several problems for Locke. Suppose the value of a finite resource, like land, is high even without human labor; assume, per example, that the intrinsic value of the land is higher than the marginal value that could be added by human labor.

U.S. property laws conform to Locke’s framework without consideration of the inequitable impacts…

Manhattan’s Central Park is an oasis of green-space surrounded by a concrete jungle of developed land and serves as a good example to highlight Locke’s fallacy. Developing this land (adding human labor) as offices, housing, agriculture, etc., would cause a net decrease in value, not only to the park but to the City. The park is not technically undeveloped—it has been landscaped, paths, drainage, etc. added, as well as utility services like water, sewage, and electrification are supplied; but it is relatively undeveloped, especially as compared to the rest of Manhattan. Treating Central Park as a common resource, applying Locke’s logic any person who fences off part of the park and uses it responsibly has taken ownership of it. This is very clearly not the case, because the relatively undeveloped land is extremely scarce in Manhattan and as such is extremely valuable, even more so prior to the application of human labor.

Locke’s logic is troubled by further problems of equity and fairness. Those who are the last to acquire a parcel of scarce, undeveloped land pay a premium, while those who acquire the land when it’s plentiful pay nothing at all. In a world with a finite resource of land, those who stake claim first hold a tremendous advantage over those who come later. Even more troubling, those born to those who stake an early claim can legally enforce their ownership claim to land on which others may be born, work, and invest their labor to the improvement and exploitation of the land. The heir who claims ownership has not invested his or her labor, as the tenant has, but still the heir is the owner, and despite any amount of labor, the tenant is not. In fact, in the case of a wealthy land-owner that owns many thousands of acres of land, maintenance, and exploitation of his or her land would be impossible without the invested labor of others. The land would “spoil.”

Locke’s declaration that permanent ownership of the finite resource of Earth’s land can be established solely by the investment of one’s labor is misguided. To do so is a de facto postulation that the resource has no intrinsic value; and further an assertion that, given responsible consumption, it is plentiful enough for everyone; both of which are self-evidently false.

Unfortunately, U.S. property laws conform to Locke’s framework without consideration of the inequitable impacts to those who do not own land; some because of poor timing, or a lack of access to resources, and some because they, or their ancestors, were denied (or delayed) the opportunity to acquire land.

The Founders of the United States have been canonized in American history for their authorship of the masterpiece documents that frame the underlying moral and legal structure of our nation; the Declaration of Independence and Constitution, including the Bill of Rights, which are so revered that Pauline Maier dubbed them “American Scripture” [4]. The American consensus seems to be that the legal framework and controls established by the founders were the altruistic expressions of great men acting outside of their own self-interest, for the good of the nation. But once King George III’s power was appropriated, it immediately fell into the hands of the wealthy planter elite. Four of the first five presidents were wealthy owners of large plantations: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe; all but the attorney, John Adams.

The outcome of the American Revolution follows George Stigler’s regulatory theory more faithfully than American Founder folklore. “His central proposition was that ‘as a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefit’” [5]. In other words, policy is adopted because the most affected stakeholders fight for their self-interest.

The same self-interest that took power from a distant king and made presidents of the rebels—the first four presidents were signatories to either the Declaration or the Constitution—also supported the institution of slavery that was the engine of their wealth, and adopted a philosophy of land ownership that served them well.

Many of the foundational philosophical pillars on which our current legal and economic system rests are based in thought that was revolutionary at the time, but has proven to be insufficient for modern times. Locke’s logic, for instance, introduced centrality of the individual over the endowment of social superiority by bloodline. Unfortunately, Lockean property rights do not eliminate bloodline superiority, but only reset it to whatever time as unclaimed property may be claimed by a claimant, for self and posterity. The resulting failure is a widening wealth gap, increasing housing affordability challenges in every major American city, and record homelessness across the U.S. We should be careful to fully understand what we believe and why.

______

[1] “U.S. Constitution,” J. United States. Congress. House. Committee on the, Ed., ed. Washington: Washington : U.S. G.P.O., 1787.

[2] J. Locke. (1689). Second Treatise to Government.

[3] T. Jefferson. (1776). Declaration of Independence.

[4] P. Maier, American scripture : making the Declaration of Independence, 1st ed. ed. New York: New York : Knopf : Distributed by Random House, Inc., 1997.

[5] J. den Hertog. U. U. Economic Institute/ CLAV. (1999). General Theories of Regulation.